During a recent visit to my studio, a friend asked me, “what is going on in this painting?” Instinctively, I drew back in silence. Like many artists, explaining a painting reverses the intended process: a painting, one hopes, is a mystery that the viewer must probe for clues, alone, without the artist’s help. Paradoxically, an artist may not entirely understand a picture’s meaning, which may extend beyond one’s original intentions. An artist can hope for an intelligent analysis by an art critic (if any know one’s work), but even that interpretation is often problematic and open to dispute.

Nevertheless, against my better judgment, I succumbed to my friend’s wishes, and explained as best I could reconstruct, what I was trying to say or express in the painting. Even as the work is being made, thoughts come and go too quickly to be recorded. Of course there is also the unconscious! Retrospectively, the best that can be done is to interpret the painting as one experiences it at that moment.

As my explanation unfolded, to my surprise and pleasure, the painting further stimulated my friend’s curiosity. She began to ask questions, even adding her own comments and interpretations to my explanation of the painting’s iconography.

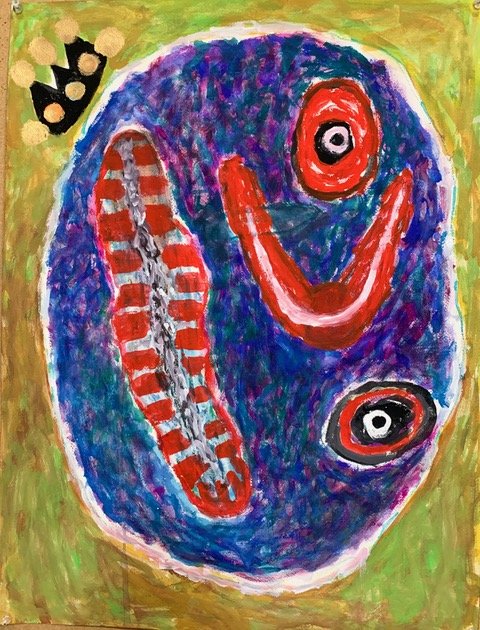

Here, in brief, is what I said or should have said had I thought of it at the time:

In the 1970’s, I had the good fortune to monitor a New School anthropology class taught by Edmund (Ted) Carpenter. The class focussed on the origins of art, going back to prehistoric cave paintings, and the diffusion of these early forms throughout primitive cultures worldwide. In that class I learned that the basis of art was the human relationship with the unknown. Art expressed the existential: life, death, survival.

I have always tried to link my artwork to these basic human facts of existence. By linking art to these essences, I hope that my work will remain relevant, and never grow old.

Here is my explanation of the artwork:

The painting tells the story of the central figure.

The sun is shining.

A figure alive. With one leg, he does a dance step.

To the right of the figure is the blue sky.

To the left of the figure are ladders. They lead into an unknown emptiness outside of the painting’s frame (death).

The figure carries death with him in the form of a black hat. Emerging from the hat are the people he has known, now recalled as memories. The figure reaches for a heart indicating that the dead as well as the living are loved.

The figure is encapsulated by a long wavy yellow line in the shape of a foot. It is the journey through life on which a driver in a car is traveling. The foot is bandaged signifying illness and mortality.

Below, a body lies interred. Brown paint and XXXs mark the soil, grave and the end of life..

Next to the body is a clock. The arrows point indicate its importance. Death is a matter of time. It is inescapable.

How does this explanation change the way a viewer sees the painting?

Marc Shanker. La Vida…Acrylic on canvas. 40” x 30.” 2020.