Signing a Painting

Why do I resist signing my name to a painting? I can’t be the only artist with this problem. I wait and wait, sometimes years, until I can barely recall when I actually completed the work.

Read More

Signing a Painting

Why do I resist signing my name to a painting? I can’t be the only artist with this problem. I wait and wait, sometimes years, until I can barely recall when I actually completed the work.

Read More

Mckee Gallery Closes Citing Art Market

Read More

STILL LIFE WITH RECORDER. OIL ON CANVAS. 1972-73.

I was reading John Elderfield’s excellent book, “The Drawings of Henri Matisse,” and came across a Matisse quotation that attracted my attention. Matisse said that In his earliest works he

“found something that was always the same which at first glance I thought to be monotonous repetition. It was the mark of my personality which appeared the same no matter what different states of mind I happened to have passed through.”

Finding and then defining this “monotonous quality” is not an easy task.

Read More

Alone, Drypoint. 8 x 10.

The Sunday, April 8th NYT Book Review offers the following quotation from author Jim Harrison who died at age 78 last month. Harrison eloquently describes the discomfort that is intrinsic to the creative process.

" In a lifetime of walking in the woods, plains, gullies, mountains, I have found that the body has no more vulnerable sense than being lost... It's happened often enough that I don't feel panic. I feel absolutely vulnerable and recognize it's the best state of mind for a writer whether in the woods or in the studio. Your mind feels a rush of images and ideas. You have acquired humility by accident. Feeling bright-eyed, confident and arrogant doesn't do this job unless you're writing the memoir of a narcissist. You are far better off being lost in your work and writing over your head. You don't know where you are as a point of view unless you go beyond yourself. It has been said that there is an intense similarity in people's biographies. It's our dreams and visions that separate us. You don't want to be writing unless you're giving your life to it."

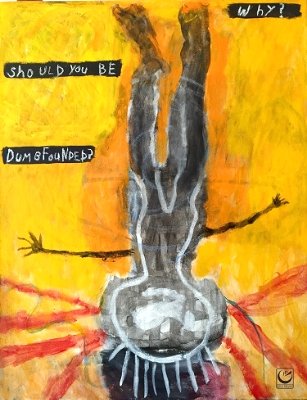

Image below is from But a Bubble, artist book by Marc Shanker, published by Gravity Free Press.

Pablo Picasso, 1937. Mother and Dead Child, Sketch for Guernica

ART THAT RATTLES

Long ago I read that art is inherently revolutionary because it challenges the viewer to rethink past assumptions about reality. The artist, in effort to find personal expression, presents a new vision or language which rattles earlier precepts, and forces the world to see itself anew.

Read More

Collaging Guston & Dubuffet

What fascinates me most about making collages is how disparate elements interact with one another to create something entirely different, unexpected, than the individual parts. The process is like a mystery unfolding in front of your eyes. And the artist is the detective. Frequently, some unnoticed mark, color or line in one element interacts with another in a way that hadn’t been anticipated. Collages have this wonderful surprise that keeps me coming back for more (Work/Collages).

In this blog, I wish to create a collage of words chosen, somewhat randomly, from the essays, lectures or interviews of two of my favorite artists: Philip Guston and Jean Dubuffet. My hope is that the juxtaposition of their words will sharpen our understanding of each artist while also broadening our view of art, and how it is made.

I will be quoting JD from the MOMA publication The Work of Jean Dubuffet, by Peter Selz with texts by the artist, and Philip Guston, Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, edited by Clark Coolidge.

Read More

SERIES: ATLAS OF THE MIND. 9 x 12" INDIA INK ON PAPER, 2014.

The creation of the “Select Series” section of my website has allowed me to show samples of related work. Often series cross or combine mediums. Some series extend to more than 100 works. Only a small selection can be offered. In a unique way, the “Select Series” section permits the viewer an intimate glimpse into how I make art, and the aesthetic or narrative values that motivate my work. It challenges the viewer to see the breadth of my work without limitations of medium, technique or aesthetic definitions.

Read More

SERIES: LUNA PARK. 22 X 31." INDIA INK ON PAPER. 2016.

Being able to work in series gives me the ability to flesh out themes, revisit compositions, explore the deeper implications of ideas, and try out new techniques. Now I was free to experiment, and to take chances. If, once again, the medium took over, it was “okay.” I’d follow it, not to the cliff’s edge or over it but to a point in the process where I learned something I needed to know. “Try it, let’s see where it goes,” became my credo.

Read More

Chatting With Images

When Gauguin left for Tahiti (1891 and 1895) “ he took with him a trunk full of photographs and reproductions of art and artifacts that he admired, as well as books, sketchbooks and manuscripts… a portable reference library he would continually turn to for inspiration” (Gauguin, Metamorphoses, MOMA, 2014). He wrote, …”I am taking a whole little world of comrades who will chat with me every day.”

Read More

A friend, after seeing one of my wax crayon drawings based on the Holocaust asked, “why do you make drawings about the Holocaust?”

I was surprised. My friend is knows the historical, philosophical and moral importance of the Holocaust. She is also knows that the Holocaust holds a personal significance for me; that the members of my family that remained in Poland and Greece were probably exterminated, and with their deaths disappeared my connection to my family’s past. Why ask a question with so obvious an answer?

I realized that I was being asked to explain why I chose the Holocaust as a subject of my art. My answer required that I recall the artistic challenges and social issues that moved me, twenty years ago, to begin this series, still ongoing, of more then thirty wax crayon and pen & ink drawings.

I explained to my friend that I was challenged by the problem of scale. How does one create an image that captures the enormity of the Nazi apparatus of death and destruction? In a work of art, can an image of one person or a group of people signify millions of victims?

A second challenge was discovering an expressive image that was neither stereotypical nor trite. There are many emotionally charged images associated with the Holocaust. I can see a few when I close my eyes. What image could I find that was unique and had a personal resonance? Additionally, the image had to have an objective basis, and be a reflection of reality, containing references, information and connections to the actual destructive process. I didn't want abstractions. I wanted essences without being pedantic.

PILE OF SPECTACLES I, PEN + INK, 22" X 26," 2014

First, I chose my medium, wax crayons, whose viscous texture soft and oily like fat and flesh. Wax crayons allow a thick surface to be built-up which can be cut or carved by a sharp pointed instrument. In this way a multiple of levels of line and imagery to be constructed, one on top of another, as if seen through a glass darkly.

Morally, I had as a humanistic goal the idea to expand the Holocaust to the world-at-large without losing its particular meaning or connection to Jews, the primary target of the Nazis genocide.

My first drawing, completed in 1997, was Pile of Spectacles. (wax crayon, 18 x 24,” MiTientes Paper). The idea to draw glasses evolved from a series of my own reading glasses that rested in front of me on my desk at work. At work, I would draw clandestinely, (co-workers called it “doodling”), whatever was close-by and unobtrusive.

As I intuitively worked on the Holocaust drawings, the pile of glasses gradually took on a number of meanings: the glasses morphed in bodies with arms and legs extended in all directions, each lens, enclosing a person’s eye--sight be a primary sense by which the world is experienced-- refers to an individual's consciousness whose voice is extinguished.

The mountainous appearance of the heap of glasses provides a feel of enormity. Something frightening is about to happen. A darkness has come over the land. Blood will be shed. The light is apocalyptic but rather than being macabre, it is an unworldly light that gives victims an anonymous presence, a dignity, and a spiritual transcendence.

The drawings, as I continued to work, evolved gradually over time. Making art is the process of allowing the unknown to become known. It is a process of self discovery.

To see additional images in this series, click here

PRINT FROM "BUT A BUBBLE." 8 X 10". TEXT IN INDIA INK.

The twenty-six dry point prints that constitute these two artist books are based upon hundreds of sketches, made of abandoned, dented and deformed bicycles, parked in long racks lining the streets of Amsterdam. I don’t know why I found the bikes a fascinating subject— perhaps because they were abandoned like orphans or ignored like pariahs? I recall that I was intrigued by their contorted forms, the way the tires were bent and twisted, often with the seat or frame still intact. I filled drawing books and sketch pads with their shapes without knowing what secret meaning the drawings held for me.

PAGE FROM DRAWING BOOK--AMSTERDAM 2009

MARKET FORCES: ECO SERIES. 47 X 53'. ACRYLIC ON CANVAS.1999.

Perhaps I was attracted because the bikes related to a series of work I completed ten years earlier, work based on how the economy is visually represented. In this early work, called Economics Series, I used pie charts, bar graphs, line charts and other visual economic descriptors. The work included many circles, a shape shared by the bicycles.

I spent nearly two years working and re-working the forms in these bicycle drawings. I varied their size and scale, moved forms around the composition, varied the qualities of the lines, and juxtaposed forms in new and unusual ways. I sketched continually, even on the subway. My purpose was to find compositions that were unusual but evocative, to see how far I could go with the subject.

Eventually, I took a selection of the drawings and used the compositions to make prints. At the print shop where I worked, my fellow print makers asked me to explain their meanings. “I have no idea,” I said. “Their meanings will have to wait until they reveal themselves.” I waited yet another year to learn their secrets.

See my forthcoming blog “Finding Meanings."

Today I turned 69, old to some, young to others. It is, nevertheless, a turning point as the 7th decade comes slowly into focus.

I’ve been making art since 1969. That’s almost fifty years, although I wasn’t fully engaged when I was young, and have had to work most of my life at 9-to-5 jobs. I have tried to live, as best I could, a life that found time for a loving, vibrant relationship, travel and intellectual growth.

For the first thirty-five years or so, I didn’t call myself “an artist.” I was "a teacher of the blind;” “finance coordinator for a union;” “ a health policy analyst;” “a communications director;” etc. Art was what I did after work, at every opportunity I could get. Weekday nights I might draw, if I wasn’t too tired, a couple of hours after dinner. Weekends gave me more time but they were especially problematical because I needed at least one day to rest. That left only one day to find the energy to resume the special mental concentration that makes creative visual work possible. Sometimes it happened, and sometimes it didn’t. The most frustrating scenario was when, after a few hours of frustrating effort, I finally got into the flow but had to quit working shortly afterwards. The next weekend I would begin the process from scratch.

It took me that many years to discover that being an artist is a slow evolution, the instilling of the process of making art in one’s being, day and night, week, month, year after year. It is an essence, like breathing, not something you do out of choice. You do it because it is your purpose, and nothing else can take its place. It isn’t easy, but that is what makes it worth while. Today, not making art is inconceivable.

I have a few close friends who respect what I have achieved. They see value in my work, and admire my talent and tenacity. But, for the most part, my career is judged “unsuccessful.” I don’t have gallery that shows my work. I sell infrequently. I am never dined, given awards, reviewed, or offered accolades. Most people aren’t even interested in visiting my studio to see what I am doing. I haven’t been told directly but I think some people believe I have spent my life pursuing a quixotic delusion. Don Quixote is my favorite book!

If my work sold, that would change things for some people. Money, what something is worth on the market, is the way everything, including art, is judged.

But at my age, selling is not my priority. Neither is showing in a gallery. What I have learned is that the joy of being an artist is having the ability to express oneself. Period. Exclamation point! That is true fulfillment, and even if my art winds-up in a landfill (ironically, the ENY housing projects where I grew-up were built on landfill), it has filled my life with such sublime happiness that I must, looking back, thank everyone who encouraged me, and give a shout out to this nation’s Bill of Rights for assuring me the right to say what is on my mind.

MoMA Café.

A few months ago, I went to MOMA to see my favorite paintings, and to eat lunch in the second floor cafeteria. Before being seated, I am always asked if I prefer a stool in the back, near the windows, or a chair next to a table. I take the table and chair.

Read MoreFranz Kafka is reported to have called Fate anything that cannot be avoided, that which is inevitable. The first thing we think of, of course, is death. This may sound grim but I find humor even in inevitability. It is an ironic, cruel humor. We make elaborate plans, and “Poof.” The juxtaposition of forethought with a lack of control creates a psychic shock. Momentarily, our plans are dislodged and we are imbalanced.

Read More

Early charcoal drawing of Faye. 1969. Included in my portfolio for art school.

In 1969, after less than six months of drawing and painting, my girlfriend, a sophisticated artist with a MFA in Fine Arts, urged me to apply to the New York Studio School in the West Village. She said I was a “natural,” who could benefit from training in a classical, figurative teaching of art. She offered to help me assemble a portfolio of my minuscule selection of work. With no idea of what art was or how it is taught in school, I agreed to apply, thinking that there was virtually no chance I would get into the program.

Read More

Envelope with postmarked stamps and person stamp. 2015.

After a time, making art becomes intuitive, meaning that most of the thinking that takes place is not rational or linguistic. Art is, after all, a visual medium not a linguistic one. But language is so deeply allied with thought that we often think in words. However, we are always using all our senses, and this form of thinking occurs “below” the linguistic level. An intuitive visual art process does not need words. Getting beyond words requires confidence in one’s perceptions and feelings.

Read More

"The Power of Hope," 24 x 30," acrylic on canvas, 2015

The power of hope overcomes the weight of impediments but must succumb to the cyclical nature of life.

Read More

Most of the time, I don't choose the colors in a painting, the colors choose me. But in accepting that choice, there is an underlying reason, sometimes visual and other times sensual, why a particular color works with a painting's composition and content.

Read More

This is an even more common question than "how do you know when a painting is finished?" My answer, without trying to circumvent the question, begins before I ever squeeze a tube of paint on my palette. In fact, it begins with the ritual of cleaning up after yesterday's efforts. I like to start each day with a clean slate regardless of whether-or-not I was successful the previous day.

Read More